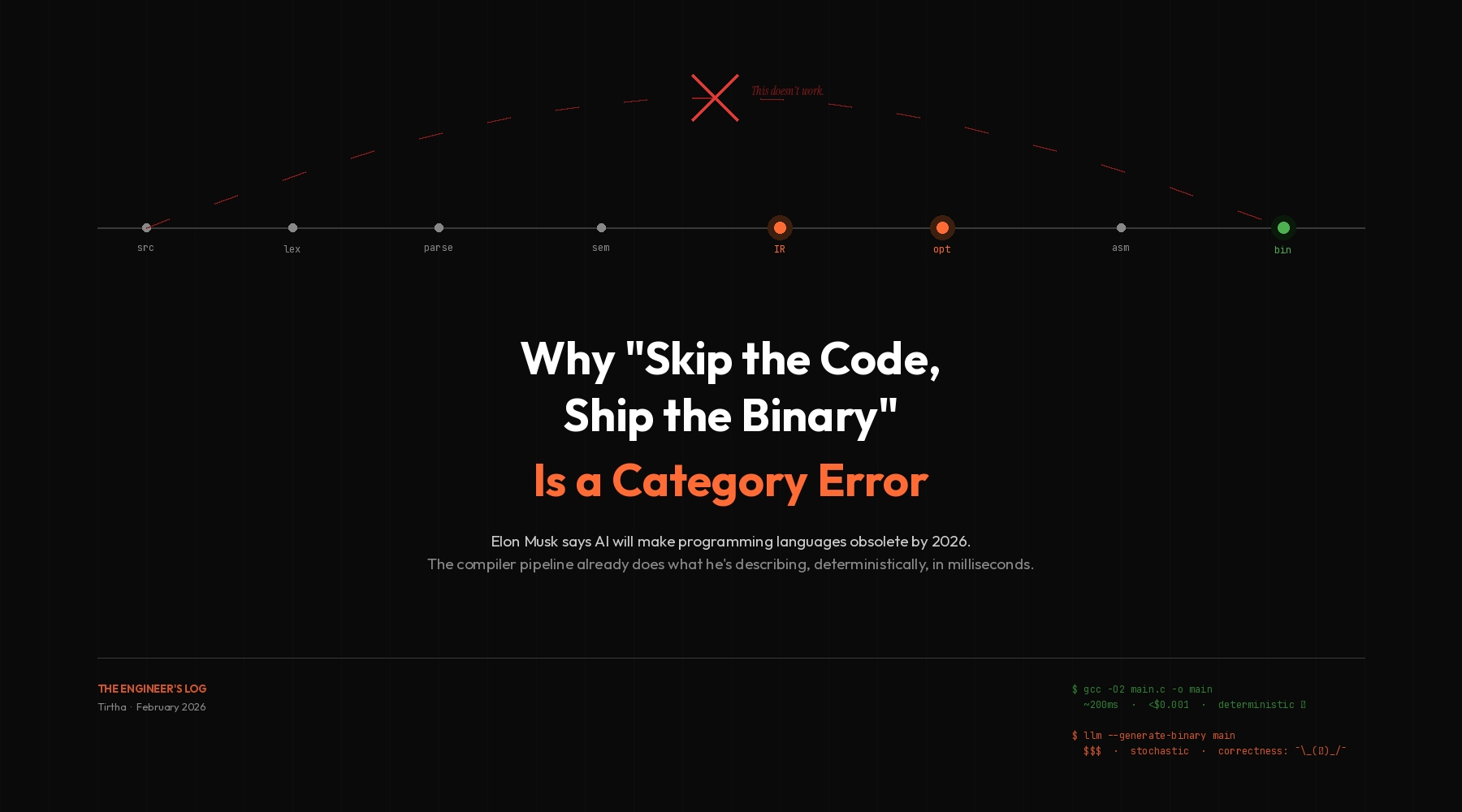

Why “Skip the Code, Ship the Binary” Is a Category Error

Elon Musk says AI will make programming languages obsolete by 2026. The compiler pipeline already does what he’s describing, deterministically, in milliseconds.

In 1952, Grace Hopper sat in front of a UNIVAC I and got tired of copying subroutine addresses by hand. Programmers at the time wrote raw machine code, looked up memory locations from a paper library, and stitched them together manually. It was slow. It was error-prone. And the errors were spectacular. “I had a running compiler and nobody would touch it,” she later recalled. “They carefully told me, computers could only do arithmetic; they could not do programs.”

She built the A-0 compiler anyway. It took symbolic mathematical code and translated it into machine instructions automatically. What previously required a month of manual coding could be done in five minutes. The skeptics told her she was confused about what computers were for. She ignored them. Within a decade, she had helped create COBOL, and the entire trajectory of software development had been permanently altered.

I bring this up because seventy-four years later, Elon Musk has essentially proposed that we undo all of it.

The Claim

At an xAI all-hands meeting this month, reported by Reuters, Musk predicted that by the end of 2026, “you don’t even bother doing coding. The AI will just create the binary directly.” He went further: “AI can create a much more efficient binary than can be done by any compiler.” The vision is straightforward. Prompt in, executable out. No source code, no compilation, no intermediate representation. Just vibes and voltage.

He also endorsed a post claiming that generating binaries directly through AI represents “the most energy-efficient approach to computing.” The next step after that, he said, would be “direct, real-time pixel generation by the neural net.”

There’s a technical term for what’s happening here, and it’s not “innovation.” It’s a category error. A compiler is a semantics-preserving transformer: it operates on a formal language with a specification, and its output is checkable against that specification. An LLM is an inference engine that produces plausible continuations of token sequences with no inherent correctness guarantee. Musk is proposing we replace the former with the latter. To understand why this falls apart, you need to understand what compilers actually do.

What Happens When You Hit Compile

Most developers have a vague mental model of compilation. You write code, you run a command, an executable appears. Magic. In reality, what happens between gcc -O2 main.c and the output binary is one of the most sophisticated chains of formal transformations in all of computer science.

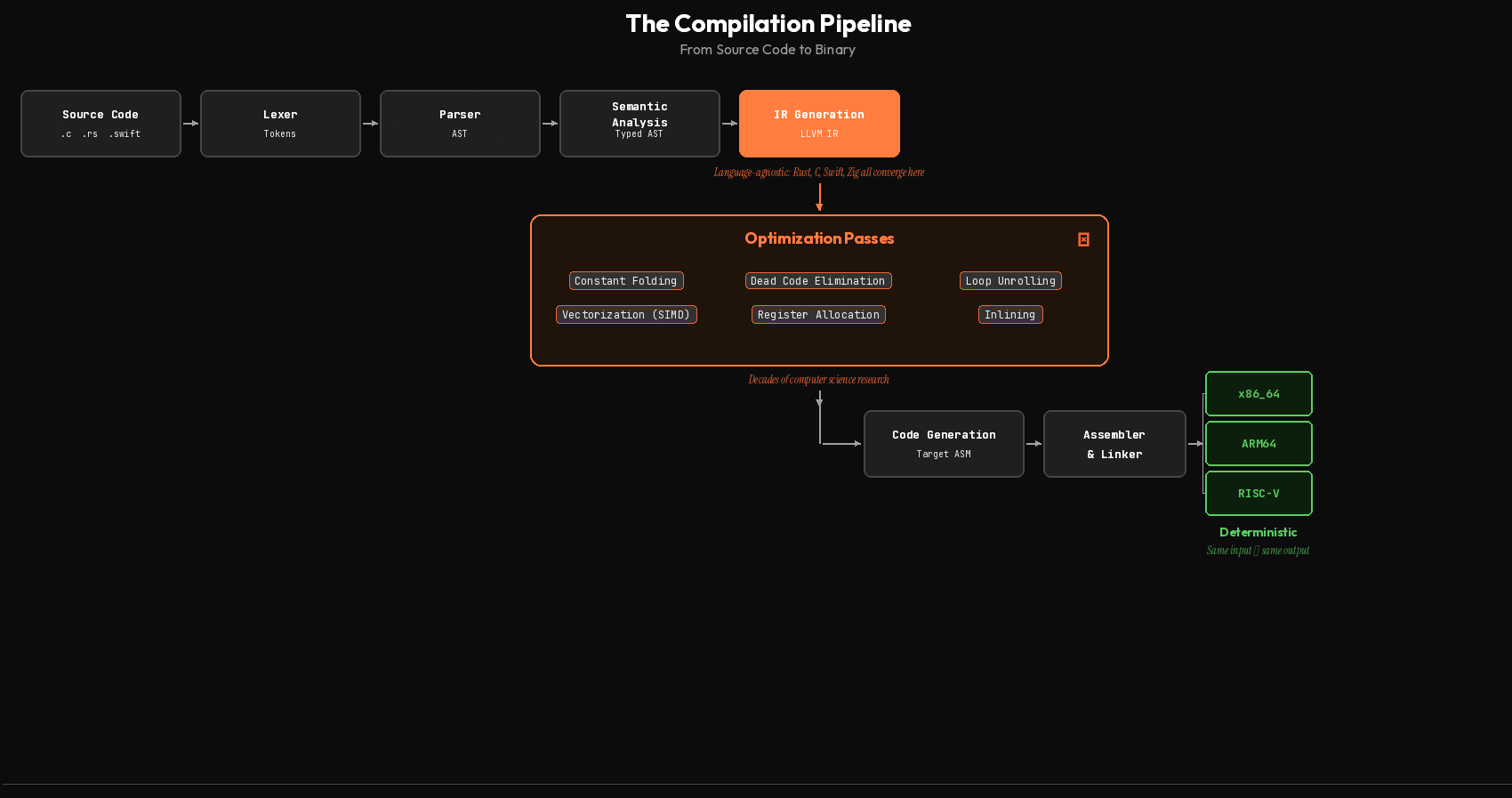

The process begins with lexical analysis: the compiler reads your source code character by character and breaks it into tokens. Keywords, identifiers, operators, literals. This is followed by parsing, where those tokens are organized into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) that represents the grammatical structure of your program. If your syntax is wrong, this is where the compiler catches it. It tells you the exact line, the exact character, and often suggests what you probably meant.

Then comes semantic analysis. The compiler checks whether your program actually makes sense. Are your types compatible? Are you referencing variables that exist? Are your function signatures consistent? This layer catches entire categories of errors early: type mismatches, undefined references, arity violations, unreachable code. Without it, those bugs surface in production, usually at the worst possible time.

After that, the compiler translates your code into an intermediate representation (IR). In LLVM, this is a typed, SSA-based format that’s independent of both the source language and the target hardware. This is the keystone of the whole architecture. Rust, Swift, C, C++, Julia, Zig, all compile down to the same IR. And once they’re there, the same optimization passes apply to all of them.

Those optimization passes are where decades of computer science research live. Constant folding: if the compiler can compute a value at compile time, it does. Write int x = 30; int y = x * 2; and the compiler just loads 60 directly into a register. No multiplication at runtime.

Dead code elimination: code that can never be reached gets deleted.

Loop unrolling: small loops get expanded to reduce branch overhead.

Vectorization: scalar operations get transformed into SIMD instructions that - process multiple data points in a single CPU cycle.

Register allocation: the compiler decides which values live in which CPU registers, solving a constraint satisfaction problem that humans gave up doing by hand in the 1970s.

Matt Godbolt’s Compiler Explorer is a beautiful window into this world. Type some C++ on the left, watch the assembly appear on the right, and toggle optimization levels to see your code transform. At -O0, you get a literal translation. At -O3, the compiler performs surgery that would take a human hours to reason about. Compiler Explorer handles 92 million compilations per year across 3,000+ compiler versions and 81 programming languages. Engineers at Google use it daily to study optimization patterns in production code.

The LLVM project alone has been in development since 2000. GCC has been around since 1987. A production-quality optimizing compiler represents decades of person-years of development. The implementation of just the basic optimization passes, constant propagation, dead code elimination, loop unrolling, register allocation, would require multiple experienced engineers working for years. And these compilers are still getting better. Both GCC and LLVM continue to improve their vectorization strategies and architecture-specific optimizations with each release.

Every single one of these transformations is deterministic. Given the same source code, the same compiler version, and the same flags, you get the same binary. (Achieving full reproducibility across build environments is its own discipline, but the compiler itself is a pure function of its inputs.) Every transformation is designed to preserve program semantics, validated by decades of testing, billions of production hours, and enormous test suites. Formally verified compilers like CompCert go further, providing mathematical proofs of correctness. Mainstream compilers like GCC and LLVM aren’t formally proven end-to-end, but they are among the most battle-tested software artifacts humans have ever produced. And it all happens in milliseconds.

This is what Musk proposes to replace. With a language model. That hallucinates.

The Economics of Stochastic Compilation

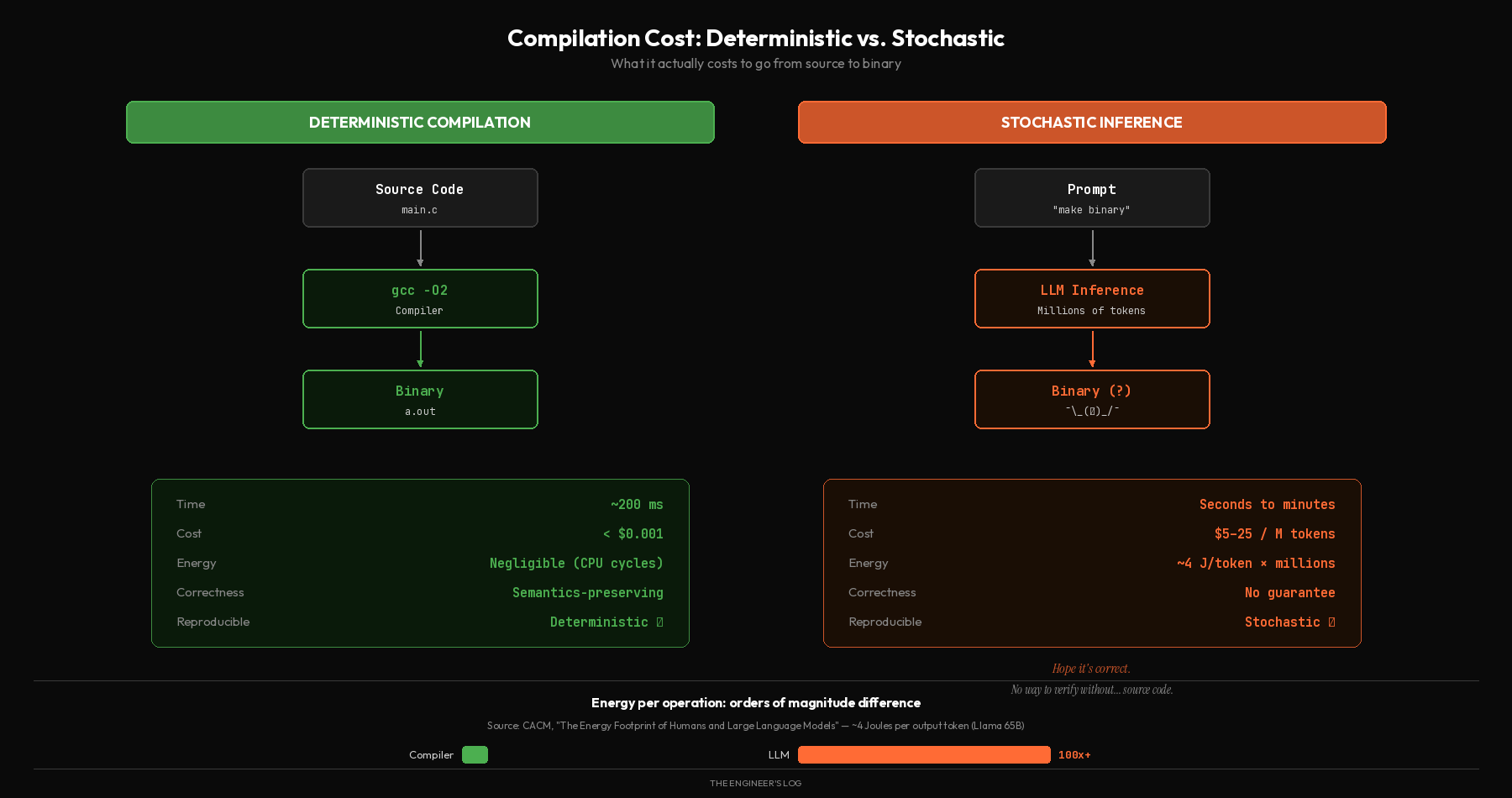

Glauber Costa, founder of Turso and a veteran Linux Kernel contributor, put it concisely on X: “The question is not whether AI will be able to ‘write the binary directly.’ The question is whether it is economical for it to do so. It costs tokens for AI to do stuff. Compiling something into binary is a solved problem and costs only CPU cycles, which are cheaper than tokens.”

This deserves unpacking because the cost differential isn’t marginal. It’s absurd.

Running gcc -O2 main.c on a reasonably complex C program takes a few hundred milliseconds of CPU time. On a cloud instance, that’s a fraction of a cent. Even compiling the Linux kernel from scratch, one of the largest compilation jobs most developers will encounter, takes minutes and costs less than a dollar in compute.

Now consider the alternative. A frontier LLM like Claude Opus 4.6 runs at $5 per million input tokens and $25 per million output tokens. A typical compiled binary for a non-trivial application might be tens of thousands of lines of machine code. To generate that “directly” as binary, the model would need to produce millions of tokens of output with perfect accuracy. Not 99.9% accuracy. Not “close enough.” Perfect. Because tiny errors in binary don’t give you a slightly wrong answer. They give you a segfault, a security vulnerability, or undefined behavior that corrupts memory in silence. And unlike a typo in source code, which a compiler flags with a helpful error on the exact line, a wrong byte in a binary gives you nothing to work with. Debugging that is archaeology, not engineering.

Even if we’re generous and assume an LLM could somehow produce correct binary output (which it cannot, but we’ll get to that), the energy economics alone are damning. Measurements with Llama 65B report around 4 Joules per output token. A modest binary might require generating millions of tokens. Meanwhile, a deterministic compiler converts the same source code to the same binary using a few hundred CPU cycles per instruction, consuming orders of magnitude less energy.

The “most energy-efficient approach to computing” argument that Musk endorsed is the exact opposite of reality. You’re proposing to replace a deterministic transformation that uses negligible compute with a stochastic inference process that requires GPU clusters running at hundreds of watts per card. That’s like saying you’ll save on shipping costs by replacing the postal service with individual helicopter deliveries.

What You Lose When You Remove Source Code

The cost argument alone should be disqualifying. But even if inference were free, the proposal would still be wrong, because it fundamentally misunderstands what source code is for.

Source code is not merely an input to a compiler. It’s the canonical artifact of software engineering. It’s the thing humans reason about, review, version, diff, debug, and maintain. Remove it, and you don’t just lose a “step in the pipeline.” You lose the entire collaborative infrastructure that makes modern software development possible.

Version control stops working. Git, the tool that underpins virtually all professional software development, works by tracking line-by-line changes to text files. You can see exactly what changed between two versions, who changed it, and why (if they wrote a decent commit message). You cannot meaningfully diff two binaries. They’re opaque blobs. Every “version” is a black box. Rollback becomes guesswork.

Code review becomes impossible. At any serious engineering organization, no code ships without peer review. A reviewer reads the diff, checks the logic, catches edge cases, and asks questions. With binary output, there is nothing to review. You’re asking engineers to trust that the AI got it right, with no way to verify. This is not a workflow. It’s a prayer.

Debugging goes from hard to impossible. When a compiled program crashes, you get a stack trace, a line number, and a variable state. When a binary-only program crashes, you get a memory address and a segfault. One of these is debuggable. The other requires a disassembler, a hex editor, and a lot of patience.

Cross-platform portability disappears. A binary compiled for x86 won’t run on ARM. A binary for ARM won’t run on RISC-V. Source code compiles to all of them with the appropriate compiler. This is, literally, one of the primary reasons high-level languages were invented. Hopper recognized in the 1950s that tying programs to specific hardware was wasteful. If your AI generates raw binary, it now needs to generate completely different outputs for every target architecture. Source code handles this abstraction for free.

Security auditing becomes a black box. You cannot audit what you cannot read. Supply chain security, already one of the hardest problems in software engineering, becomes effectively impossible when every artifact is an opaque binary produced by a non-deterministic process. How do you verify that the AI didn’t introduce a vulnerability? How do you even define “vulnerability” when you can’t inspect the logic?

Hopper understood this in 1952. The whole point of moving away from machine code was to give humans a way to reason about what computers were doing. Programming languages aren’t a limitation to be overcome. They’re a communication protocol between humans and machines. Removing the human-readable layer doesn’t simplify anything. It blinds you.

What LLMs Actually Do Well (And It’s Not This)

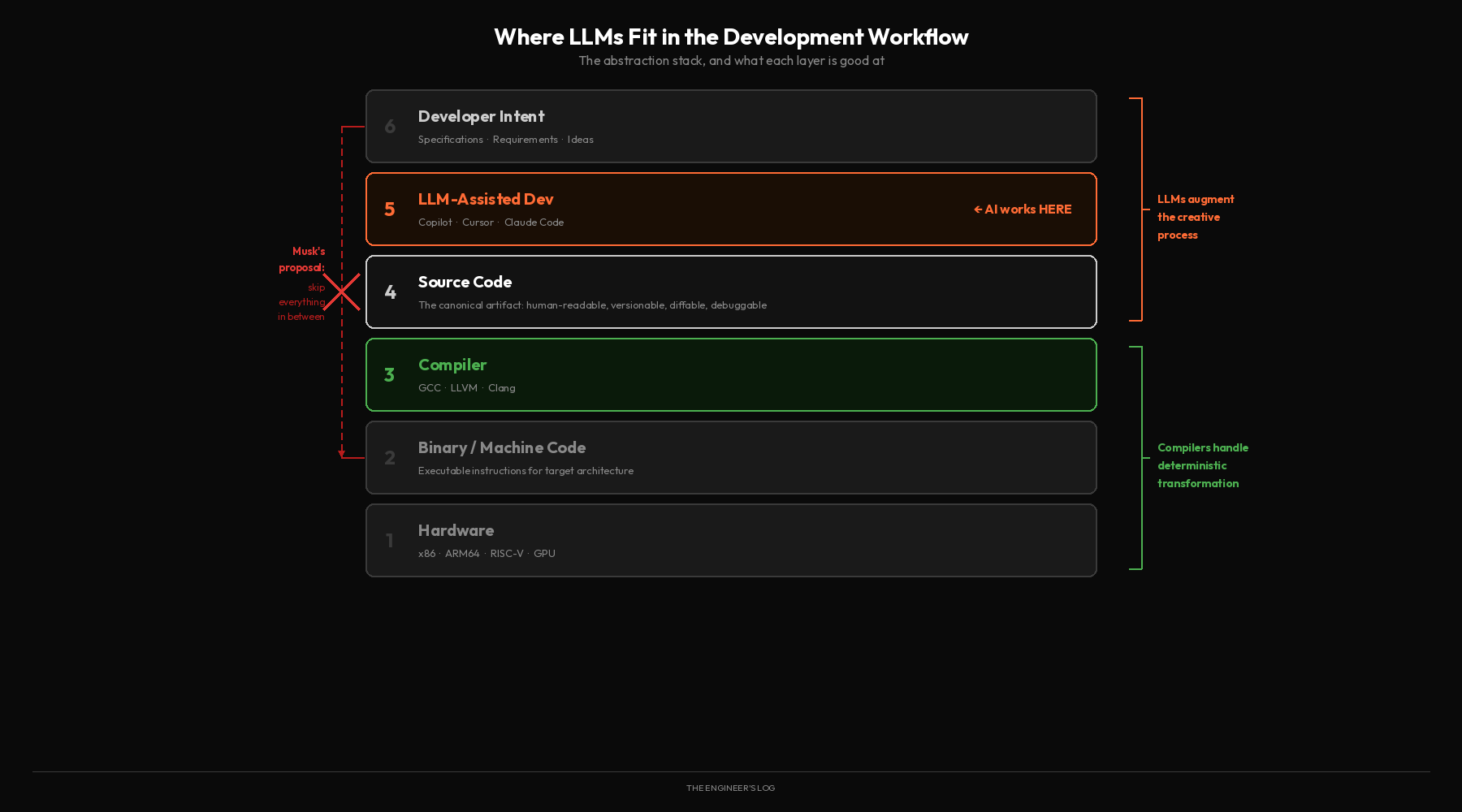

Here’s the thing: LLMs are genuinely transforming software development. I use them every day. They’re remarkable tools. And the way they’re actually useful has nothing to do with “skipping code and generating binary.”

LLMs excel at working within the existing abstraction stack, not at replacing it. They’re very good at generating boilerplate code, discovering APIs, prototyping quickly, translating between programming languages, explaining unfamiliar codebases, and writing tests. They’re particularly good at the parts of programming that are tedious but well-patterned, the kind of work where a developer already knows what to write but doesn’t want to type it out.

This is valuable. It makes developers faster, lowers barriers to entry, and lets experienced engineers spend more time on architecture and design. The tooling around LLM-assisted development, things like Cursor, GitHub Copilot, and Claude’s agentic coding capabilities, is getting better at a rapid pace.

But notice what all these tools produce: source code. Human-readable, version-controllable, reviewable, debuggable source code. That code then gets compiled by deterministic compilers into optimized binaries. The LLM handles the creative generation. The compiler handles the deterministic transformation. Each does what it’s good at.

There’s genuinely exciting research at the intersection of LLMs and compilation. VecTrans, a framework presented in 2025, uses LLMs to refactor code into patterns that are more amenable to compiler auto-vectorization, achieving a 1.77× geometric mean speedup. LLM-Vectorizer takes a similar approach, using LLMs to generate SIMD intrinsics with formal verification through Alive2 to guarantee correctness. But notice the pattern in both: the LLMs are generating source-level code that then goes through the traditional compilation pipeline. They’re augmenting the compiler, not replacing it.

As Costa noted: “If AI would become better at compiling code than current compilers, then it would write a compiler and from that moment on, use that.” The optimal use of AI in the compilation chain is to improve the tools, not to become a worse version of them.

But What If He Doesn’t Mean It Literally?

A generous reading of Musk’s claim might go something like this: “He doesn’t literally mean sampling random bits. He means AI-assisted compilation, or program synthesis, or some kind of end-to-end system that takes intent and produces executables.”

Fair enough. Let’s steelman it.

If you mean AI that improves compilers, that’s already happening. The research I just cited shows LLMs helping with vectorization decisions, optimization pass ordering, and code refactoring for better compiler cooperation. This is real, useful, and incremental. It’s also not what Musk described. He said “you don’t even bother doing coding,” not “compilers get smarter.”

If you mean program synthesis from formal specifications, that’s an active research area with decades of history. Systems like Sketch and modern synthesis tools can generate programs from constraints. But they work precisely because they have formal specifications to verify against. The output is checked, not trusted. And the specifications themselves are written in structured, human-readable languages. You still need the human-readable layer.

If you mean end-to-end binary generation from natural language prompts, with no source code, no formal specification, and no verification step, then you’ve arrived at Musk’s actual claim, and it collapses under the problems I’ve already described. A recent survey of LLM-compiler research puts it plainly: current approaches “mostly cannot surpass traditional compilers in either performance, cost or scalability” even on narrow compilation tasks, let alone end-to-end generation.

The steelmanned versions either aren’t what he said or aren’t new. The literal version is what he said and doesn’t work.

Why He’s Saying This

Musk claims he built video games as a kid. If that’s true, none of this should be foreign to him. He’s written code. He’s dealt with compilers. He presumably understands the difference between a deterministic process and a probabilistic one.

But “AI helps developers write better code faster” is not a useful narrative if you’re running xAI. It doesn’t move Grok’s positioning. It doesn’t justify the billions in GPU infrastructure. It doesn’t make headlines.

“AI kills coding entirely” does all three.

This isn’t unique to Musk. Every company building GPU infrastructure has an incentive to claim that everything will require inference compute. When the business model depends on selling tokens, every problem looks like it needs more tokens. Musk runs xAI. Grok needs a story. And every claim about AI’s imminent omnipotence is also a claim about the value of the infrastructure xAI is building. When you tell the world that AI will replace compilers, generate binaries directly, and eventually produce real-time pixel output from neural nets, you’re not making a technical prediction. You’re making an investment thesis. You’re telling the market that the demand for inference compute is about to become essentially infinite, that every act of creation, from writing code to rendering graphics, will soon require running through an LLM.

Musk has a history of predictions with ambitious timelines. Fully autonomous vehicles by 2018 (still not here). A million robotaxis on the road by 2020 (laughable in hindsight). Human-machine symbiosis via Neuralink by 2021 (we’ve managed to let a few people move cursors). These predictions aren’t meant to be accurate. They’re meant to be directional, to shape expectations and investment around a particular vision of the future, one in which his companies are central.

The “coding goes to zero” claim is the same play. It’s not a technical analysis. It’s demand generation for inference compute, dressed up as prophecy.

The Actual Future

The future of programming is not binary generation from prompts. It’s what’s already happening: higher-level abstractions, better tooling, and AI as a collaborator in the creative process of writing software.

Programming languages will continue to evolve. Compilers will continue to improve, potentially with ML-assisted optimization passes that discover new transformations. LLMs will continue to get better at generating, reviewing, and explaining code. The gap between “I have an idea” and “I have working software” will continue to shrink.

But source code isn’t going anywhere. It exists because humans need to understand, verify, and maintain what computers do. That need doesn’t go away because the computers got smarter. If anything, it gets more important.

Grace Hopper spent her career fighting for the idea that programming should be accessible, that humans should be able to express their intent in languages they can read and reason about, and that machines should handle the translation to hardware. She was right then, and the principle holds now.

The answer to “how do we make software development better” is not “remove the human’s ability to understand the software.” The answer is better tools, better languages, better compilers, and yes, better AI assistants that work within the stack rather than trying to replace it.

Musk’s prediction will age the way his other predictions have aged: as a reminder that the loudest voices in tech are often the least interested in how things actually work.